Ivan Henry’s ordeal

May 16, 2014 in Opinion

Ivan William Mervin Henry was incarcerated for almost 27 years in respect of crimes he did not commit. He was ultimately acquitted by the Court of Appeal on October 27, 2010 but has not received any compensation from the state for the miscarriage of justice that occurred in his case. Here is a timeline of some of the events in the saga:

1980-1982: Dozens of sexual assaults with a similar distinctive modus operandi occur in Vancouver.

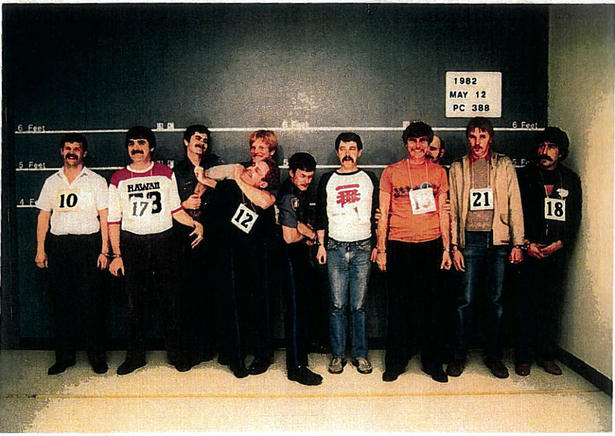

May 12, 1982: Mr. Henry is arrested by Vancouver police and forced into a physical lineup viewed by several victims.

Ivan Henry is number 12 in this lineup photograph introduced into evidence at his 1983 criminal trial.

July 29, 1982: Mr. Henry is charged with 17 counts of sexual assault and arrested.

February 28-March 15, 1983: Mr. Henry is tried by Mr. Justice Bouck and a jury on ten counts. Michael Luchenko and Judith Milliken are the prosecutors; Mr. Henry represents himself. The Crown adduces no physical evidence linking Mr. Henry to any of the crime scenes or assaults (although perpetrator semen and other physical evidence was retrieved during the investigation) and relies only on the testimony of the complainants. Mr. Henry is found guilty of all charges on March 15, 1983 and remains in custody for sentencing.

April 12, 1983-July, 1988: More than two dozen similar sexual assaults are perpetrated in Vancouver while Mr. Henry remains in custody.

November 23, 1983: Mr. Henry is declared a dangerous offender and sentenced to an indefinite period of incarceration.

February 24, 1984: The Court of Appeal grants the Crown’s application to have Mr. Henry’s appeal from conviction dismissed for want of prosecution after he failed to obtain the trial transcripts.

November 24, 2004: Following a review of historic sexual assault cases, Donald James McRae is charged with three sexual assaults from the 1980s.

May 27, 2005: Mr. McRae pleads guilty to the charges and is sentenced to five years in prison.

November 15, 2006: Lawyer Leonard Doust Q.C. is appointed by the Criminal Justice Branch of the Ministry of Attorney General for BC to review Mr. Henry’s case to determine “whether there had been a potential miscarriage of justice.”

March 28, 2008: The Criminal Justice Branch releases a summary of Mr. Doust’s recommendations.

January 13, 2009: The Court of Appeal orders that Mr. Henry’s appeal be re-opened. Mr. Henry is released on bail pending the hearing of his appeal, with an electronic monitoring bracelet attached to his leg.

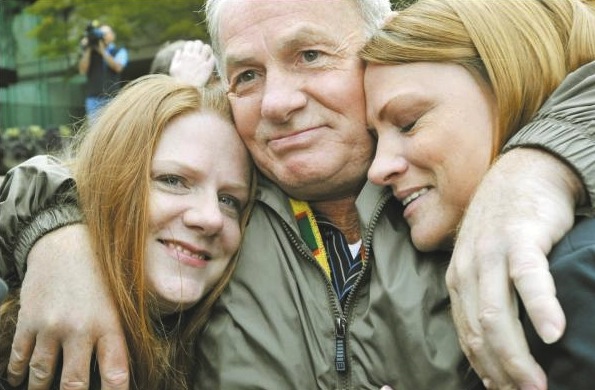

October 27, 2010: The Court of Appeal allows the appeal, sets aside the verdicts and enters acquittals, stating, among other things, “the verdict on each count was not one that a properly instructed jury acting judicially could reasonably have rendered.”

Ivan Henry with his daughters upon his acquittal and release from prison in 2010

June 28, 2011: Mr. Henry files a civil lawsuit seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction. The defendants include the City of Vancouver, the Attorney General of British Columbia and the Attorney General of British Columbia.

April 18, 2013: The BC Supreme Court decides that Mr. Henry’s claim for Charter damages against the Crown prosecutors can succeed if he establishes at trial that their conduct amounted to a marked departure from the standards expected of them.

January 21, 2014: The Court of Appeal finds the BC Supreme Court judge erred in in its decision and holds that Mr. Henry has to establish malice on the part of the trial prosecutors to succeed against the provincial Crown.

May 15, 2014: The Supreme Court of Canada allows Mr. Henry’s application for leave to appeal the Court of Appeal’s decision. The appeal is set for hearing in November of 2014. Mr. Henry’s civil claim for compensation is now scheduled to proceed to a 100 day trial commencing August 31, 2015.

May 1, 2015: Mr. Henry wins the Supreme Court of Canada case, the court overturning the Court of Appeal’s decision and holding that can be entitled to Charter damages absent prosecutorial malice.

June 1, 2016: Following a lengthy trial in the BC Supreme Court, Mr. Henry wins his case and is awarded over $8 million in damages for wrongful conviction.

Therefore, Ivan Henry lived under a cloud, asserting his innocence for 34 years, before justice was finally served and he received compensation.

posted by Cameron Ward

Supreme Court of Canada grants Ivan Henry leave to appeal

May 15, 2014 in Opinion

Today, the Supreme Court of Canada granted our client Ivan Henry’s application for leave to appeal a January 2014 decision of the British Columbia Court of Appeal that would have affected his civil claim for compensation for his wrongful conviction. Mr. Henry was acquitted and freed by the Court of Appeal in a 2010 decision, but the government refused to pay him any compensation for the 27 years he spent behind bars.

Mr. Henry brought a lawsuit for damages, which was scheduled to proceed to trial on September 8, 2014, but he will likely now have to wait another year or so for his day in court.

The Supreme Court of Canada’s description of the case:

Charter of rights – Crown law – Crown liability – Applicant wrongfully convicted and incarcerated during almost 27 years – Subsequent civil claim against provincial Crown for, inter alia, malicious prosecution and seeking Charter damages for non-disclosure of evidence at trial – Whether Crown prosecutors liable for anything less than malicious prosecution – Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, ss. 7, 11(d), 24(1).

Mr. Henry was convicted in 1983 of 10 sexual offence counts, was declared a dangerous offender and sentenced to an indefinite period of incarceration. He remained incarcerated for almost 27 years, until granted bail in 2009, and was acquitted in October 2010. Mr. Henry then sought damages against, inter alia, the prosecutors for the injuries he alleges he suffered as a consequence of the wrongful conviction and incarceration. The claim relates to the actions of Crown counsel through the course of the trial and subsequent appeal processes.

Mr. Henry is seeking damages under s. 24(1) of the Charter and, to that end, successfully applied for leave to amend his pleadings to include the following:

120. The various acts and omissions that violated the Plaintiff’s right to disclosure and/or his right to full answer and defence and/or his right to a fair trial, as described in paragraphs 113-119 above, were a marked and unacceptable departure from the reasonable standards expected of the Crown counsel.

The amendment was subsequently refused by the B.C. Court of Appeal, on the basis that Supreme Court authority currently forecloses prosecutorial liability for negligence and requires evidence of malice.

Follow this site using RSS

Follow this site using RSS