Ivan Henry civil trial date set

January 30, 2013 in News

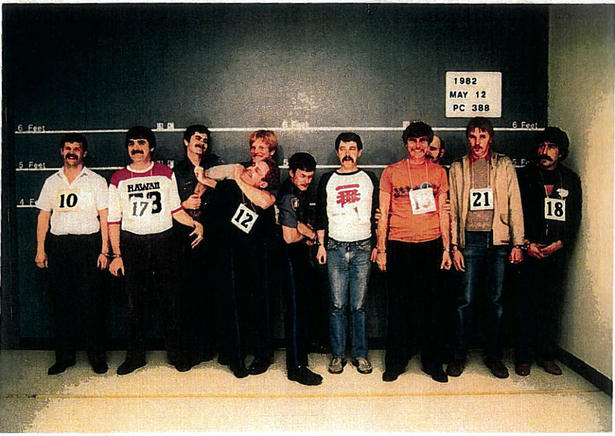

Ivan Henry is number 12 in this lineup photograph introduced into evidence at his 1983 criminal trial.

Rejean Hinse, with Edvard Munch's "The Scream"; CBC

posted by Cameron Ward

Public inquiries – useful, or a waste of time and money?

January 18, 2013 in Opinion

Now that a month has passed since the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry report was released to the public, it may be time to reflect on whether there is any point in holding more provincial public inquiries in the future. From my perspective as counsel for the families of scores of women who were murdered in Port Coquitlam by Robert William Pickton and persons unknown, the MWCI was an abject and profoundly disappointing failure. I can only hope that, for my clients’ sake, the government quickly implements the recommendations that the families receive financial compensation for the loss of their loved ones so that the healing process can continue.

That said, I still believe that a public inquiry can be an important way to address public concerns arising from any particular scandalous event. The process has two main purposes; first, to conduct a thorough and independent investigation into what actually happened and, second, to make recommendations to ensure something similar doesn’t happen again. Although the MWCI completely failed on the first front, that doesn’t mean that future inquiries need to founder on the same shoals. The government must ensure that the tribunal it appoints is completely independent, fully committed to the process and has the necessary time and resources to fulfill its duty to the public. In the end, like any human endeavour, the success of a public inquiry will depend on the integrity, diligence, commitment and good faith of the participants.

Critics refer to the cost of the undertaking and suggest that the money could be better spent elsewhere. They have a point, but one can’t put a price tag on truth and justice. One can, however, impose reasonable spending limits and ensure that taxpayers receive value for their money.

Public inquiries can still work in B.C. I was one of the lawyers involved in the inquiry into the death of Frank Paul, who died of hypothermia in a Vancouver alley after being dumped there by the police. Commissioner William Davies, Q.C. presided over the inquiry into the scandal firmly and fairly, with a judicial demeanour acquired over years on the bench of the B.C. Supreme Court. His Commission Counsel, including Geoff Cowper, Q.C. and Brock Martland, marshalled and presented the relevant evidence and pursued the true facts fearlessly and without favouritism. They didn’t attempt to delegate their important fact-finding responsibility to other so-called “expert” investigators. The Frank Paul Inquiry made some important recommendations, one of which, the creation of the Independent Investigations Office, should improve the public perception of police in the province. The FPI wasn’t perfect – no human endeavour is – but it demonstrates that the public inquiry can serve as a vehicle for exposing the truth and shouldn’t be abandoned just yet.

posted by Cameron Ward

Ferry sinking trial begins – but why has it taken so long?

January 17, 2013 in Opinion

The trial of Karl Lilgert on two counts of criminal negligence causing death arising from the March 22, 2006 sinking of The Queen of the North reportedly began today. It should not have taken almost seven years to put the accused on trial. This delay, which includes some four years of investigation before the charges were even laid, is unacceptable and gives our criminal justice system a black eye. All the participants in the system -police, prosecutors, defence lawyers, public – have to come up with ways to speed up the glacial pace of justice in cases like this.

posted by Cameron Ward

MWCI: Final report released

December 18, 2012 in Missing Women Commision of Inquiry, News

The final report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, very aptly entitled “Forsaken” was released to the public yesterday and is available here.

We may comment in due course.

posted by Cameron Ward

MWCI report release imminent

December 6, 2012 in Missing Women Commision of Inquiry, Opinion

Update: The government has issued a news release updating its arrangements for the families of the murdered women and facilitating their access to the Commission’s final report.

………

We have been advised that the final report of the Missing Women Commission Inquiry will be released to the public soon. The provincial government received the 1,448 page document in November and will apparently give us, the lawyers for the families of 25 of the murdered women, an hour to read the report before it is released to the public and live-streamed on the internet.

This approach is in keeping with the Commission’s general attitude toward the families of the missing and murdered women. The MWCI paid lip service to our clients’ concerns, but it conducted an “inquiry” that barely scratched the surface of its mandate. That mandate, as set out in the Terms of Reference, required the Commission:

“(a) to conduct hearings, in or near the City of Vancouver, to inquire into and make findings of fact respecting the conduct of the missing women investigations;

(b) consistent with the British Columbia (Attorney General) v. Davies, 2009 BCCA 337, to inquire into and make findings of fact respecting the decision of the Criminal Justice Branch on January 27, 1998, to enter a stay of proceedings on charges against Robert William Pickton of attempted murder, assault with a weapon, forcible confinement and aggravated assault.”

The Vancouver Police Department and the RCMP knew by March 17, 1997 that Robert William Pickton had taken a survival sex trade worker (by definition, a desperate woman who would turn tricks for as little as two dollars just to survive on Vancouver’s Skid Row) to a suburb some 45 minutes away by car, where he attempted to murder her. The police also knew that Robert William Pickton and his brother David Francis Pickton operated a notorious hangout known as “Piggy’s Palace” which was reportedly frequented by off duty police officers, members of a criminal gang and sex trade workers. The brothers also operated an excavation business. Scores of survival sex trade workers went missing from Vancouver until February 5, 2002, when a rookie Coquitlam RCMP member, Cst. Nathan Wells, “accidentally” discovered evidence of the murders on the Pickton brothers’ ramshackle property.

After a year long trial, Robert William Pickton was convicted of six counts of second degree murder. The province’s Attorney General stayed twenty counts of first degree murder. Although Pickton’s jury obviously concluded that he did not act alone, nobody else was ever tried for the murders of as many as fifty women. The public inquiry was called after Pickton’s final appeal was dismissed by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Some things to look for in the report:

The government and the Commissioner, former Liberal Attorney General Wally Oppal Q.C., will point to the number of hearing days, witnesses and pages in the report to suggest that the inquiry was thorough and exhaustive. We submit that the report should be read with the following points in mind:

1) The real reason why Pickton wasn’t put on trial for attempted murder as a result of his 1997 attack. The victim was credible, ready and willing to testify and, with standard witness management techniques, could have been put on the witness stand. Instead, Crown Counsel dropped the case like a hot potato.

2) The role that sexism and misogyny played in the inadequate police investigations. The VPD had one detective on the case, who eventually quit in frustration. She later wrote an unpublished book about her experience, in which she concluded that her male colleagues “wouldn’t have pissed on the [missing women] if they were on fire.”

3) The Coquitlam RCMP’s knowledge of the wild parties at Piggy’s Palace. The RCMP had a long serving civilian worker within the small Coquitlam detachment who lived near the Pickton brothers and knew them intimately. She conveyed information to RCMP members, but it wasn’t acted on.

4) The long association between the Pickton brothers and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club. Former RCMP Deputy Commissioner Gary Bass testified that the RCMP routinely infilitrates and monitors the activities of the HAMC.

5) The failure to obtain a search warrant sooner. Cst. Wells swore an information to obtain the search warrant that snared Pickton in 2002, yet the RCMP had the same information in their hands by July of 1999.

Follow this site using RSS

Follow this site using RSS