Ivan Henry civil trial date set

January 30, 2013 in News

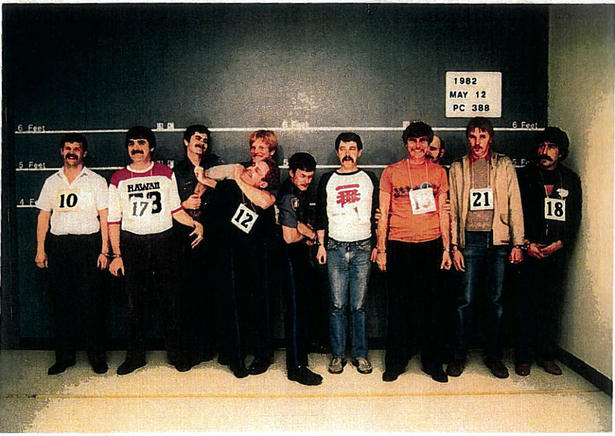

Ivan Henry is number 12 in this lineup photograph introduced into evidence at his 1983 criminal trial.

Rejean Hinse, with Edvard Munch's "The Scream"; CBC

posted by Cameron Ward

Public inquiries – useful, or a waste of time and money?

January 18, 2013 in Opinion

Now that a month has passed since the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry report was released to the public, it may be time to reflect on whether there is any point in holding more provincial public inquiries in the future. From my perspective as counsel for the families of scores of women who were murdered in Port Coquitlam by Robert William Pickton and persons unknown, the MWCI was an abject and profoundly disappointing failure. I can only hope that, for my clients’ sake, the government quickly implements the recommendations that the families receive financial compensation for the loss of their loved ones so that the healing process can continue.

That said, I still believe that a public inquiry can be an important way to address public concerns arising from any particular scandalous event. The process has two main purposes; first, to conduct a thorough and independent investigation into what actually happened and, second, to make recommendations to ensure something similar doesn’t happen again. Although the MWCI completely failed on the first front, that doesn’t mean that future inquiries need to founder on the same shoals. The government must ensure that the tribunal it appoints is completely independent, fully committed to the process and has the necessary time and resources to fulfill its duty to the public. In the end, like any human endeavour, the success of a public inquiry will depend on the integrity, diligence, commitment and good faith of the participants.

Critics refer to the cost of the undertaking and suggest that the money could be better spent elsewhere. They have a point, but one can’t put a price tag on truth and justice. One can, however, impose reasonable spending limits and ensure that taxpayers receive value for their money.

Public inquiries can still work in B.C. I was one of the lawyers involved in the inquiry into the death of Frank Paul, who died of hypothermia in a Vancouver alley after being dumped there by the police. Commissioner William Davies, Q.C. presided over the inquiry into the scandal firmly and fairly, with a judicial demeanour acquired over years on the bench of the B.C. Supreme Court. His Commission Counsel, including Geoff Cowper, Q.C. and Brock Martland, marshalled and presented the relevant evidence and pursued the true facts fearlessly and without favouritism. They didn’t attempt to delegate their important fact-finding responsibility to other so-called “expert” investigators. The Frank Paul Inquiry made some important recommendations, one of which, the creation of the Independent Investigations Office, should improve the public perception of police in the province. The FPI wasn’t perfect – no human endeavour is – but it demonstrates that the public inquiry can serve as a vehicle for exposing the truth and shouldn’t be abandoned just yet.

posted by Cameron Ward

Ferry sinking trial begins – but why has it taken so long?

January 17, 2013 in Opinion

The trial of Karl Lilgert on two counts of criminal negligence causing death arising from the March 22, 2006 sinking of The Queen of the North reportedly began today. It should not have taken almost seven years to put the accused on trial. This delay, which includes some four years of investigation before the charges were even laid, is unacceptable and gives our criminal justice system a black eye. All the participants in the system -police, prosecutors, defence lawyers, public – have to come up with ways to speed up the glacial pace of justice in cases like this.

posted by Cameron Ward

Forsaken again: the MWCI was a missed opportunity for truth and reconciliation

December 19, 2012 in Missing Women Commision of Inquiry, Opinion

Families and supporters of the missing women at Monday’s press conference (Photo by Carmine Marinelli/24 Hours)

Monday’s press conference for the release of the Commissioner’s final report confirmed the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry was a missed opportunity to ameliorate relationships between the victims’ families, community groups, police departments and the Provincial Government. The Commissioner was hardly through his introductory remarks when heckling from the public gallery began. Outside the press conference, dozens protested and distributed leaflets calling for a national inquiry into the ongoing crisis of murdered and missing women, suggesting little has changed since the Inquiry was first called.

The final report is lengthy—bound in 6 volumes including a 150-page executive summary—but its size belies its fatal flaw: the foundation of the report is incomplete. Early funding decisions by the Provincial Government effectively excluded most community groups from the evidentiary hearings. During those hearings, the Commission refused to hear from important witnesses and refused to compel relevant records that were essential to its fact-finding mandate. Independent counsel for aboriginal interests, Robyn Gervais, resigned from her position in protest. Decisions made by the Commission respecting the design and conduct of this public inquiry critically wounded its perceived integrity. The Commission failed to complete its important work.

The final report includes a thorough review of the evidentiary record, albeit incomplete, and a satisfactory recitation of “what happened” in the course of the impugned missing women investigations. Police failure after police failure is described in detail: poor report taking and follow up on reports of missing women; faulty risk analysis and risk assessments; inadequate proactive strategies to prevent further harm; failures to consider all investigative strategies; failures to follow Major Case Management practices; failures to address cross-jurisdictional issues and ineffective coordination between police forces and agencies; and failures of internal and external accountability mechanisms. The respective police departments ought to be humbled by these findings.

One area where the report falls short, however, is in explaining “why” these failures occurred. Of the report’s 1448 pages, only 65 are dedicated to the “Underlying Causes of the Critical Police Failures” – the title of Part 4, Volume II. More importantly, the Commissioner fails to find direct or overt discrimination played a role in the failed missing women investigations, and refuses to attribute blame for the failed investigations to any specific individuals, or even the police departments themselves. For the families, this was a missed opportunity for truth and reconciliation.

The answers to the “why” question are critical because they are necessary to lay the foundation for recommendations for change. Without a proper understanding of why the missing women investigations failed, police and governments will not be able to prevent another similar tragedy from occurring. In the Commissioner’s own words:

“There is great public utility in addressing allegations that bias, sexism and racism had some role in the police failures: a more profound and complete understanding of the past creates the foundation for learning, which leads to positive change in the future.”

Indeed, the Commissioner has acknowledged to some degree that bias, sexism and racism were to blame for the “colossal failure” of the missing women investigations. The public gallery on Monday gave a singular cheer at the Commissioner’s pronouncement that “systemic bias” contributed to this failure. For our clients, this finding is merely confirmation of something they have long known: police prejudices involving aboriginal women, sex trade workers and drug users affected decisions at every stage of the missing women investigations. There is no doubt these investigations would have been conducted differently had the women been reported missing from another, more privileged neighbourhood.

The Commissioner is, however, quick to qualify his finding of “systemic bias” in the final report:

“The systemic bias operating in the missing women investigations was a manifestation of the broader patterns of systemic discrimination within Canadian society and was reinforced by the political and public indifference to the plight of marginalized female victims.”

In effect, the Commissioner deflects blame away from the police and onto society at large. The bias was not “institutional”, it was “systemic”, as the police departments mirrored the prejudices of society at large, says the report. The Commissioner adopts a phrase from Sir Robert Peel: “the police are the public and the public are the police”, and goes on to say “[t]he police failures in this case mirror the general public and political indifference to the missing women. […] At some level, we all share the responsibility for the unchecked tragedy of the failed missing women investigations.”

The families find this hard to swallow. Surely their desperate pleas to police for help finding their missing daughters, sisters and mothers were not indifferent? Surely the women and men marching in the streets demanding action were not indifferent? And shouldn’t the police be held to a higher standard than the general public? How can the indifference shown by police be justified as being a reflection of public opinion?

In our view, the numerous police failures found by the Commissioner in his final report are better characterized as manifestations of institutional and individual police biases. Police policies, practices, and culture were to blame for these failures, not society at large. Individual officers made critical decisions not to follow up on tips, not to allocate resources, and not to warn the public. The Commissioner’s hesitation to attribute fault was a missed opportunity, and weakens the foundation for the recommendations that follow.

The families applaud the Commissioner’s recommendations for increased funding to centres providing emergency services to women, restorative measures, equality-promoting measures, measures to enhance the safety of vulnerable urban women, and measures to prevent violence against aboriginal and rural women, among the many other recommendations outlined in Volume III the report. It remains to be seen, however, whether the foundation of this report has the structural integrity to support any significant improvements to the lives of disadvantaged women.

posted by Neil Chantler

MWCI: Final report released

December 18, 2012 in Missing Women Commision of Inquiry, News

The final report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, very aptly entitled “Forsaken” was released to the public yesterday and is available here.

We may comment in due course.

Follow this site using RSS

Follow this site using RSS